Green light to a dead end

So the president is cock-a-hoop about the matric results. And playing the race card again by accusing the Opposition leader of not being able to accept that blacks are able to pass exams.

But Helen Zille has good reason to be sceptical about the statistics. Her own province, which regularly has had the best results, is suddenly fourth behind certain ANC strongholds. Also (surprise! surprise!) Limpopo has registered a 71.8 per cent pass rate, although pupils in the province were denied text books for most of the year!

Almost as bad as this clear manipulation is the news that some provinces have been culling numbers before the exams, telling Grade 11 pupils who might fail that they will not even get a chance to write matric. How cynical is that?

The biggest problem with our education, of course, is that many thousands of the pupils who have been allowed to write, and successfully, will merely have been given a green light into a dead end.

That problem will persist until the country as a whole comes up with a better programme of job creation. To that end, the government could help by looking to develop the state land it has appropriated over two decades, setting up and training youngsters on community farms.

The Israeli government would be able to assist, and might be pleased to do so. Its kibbutzim were at the heart of that country’s own agricultural development and still employ many young citizens.

But then Jacob Zuma and his acolytes are unlikely to approach Israel. For them it is a state non grata for a couple of reasons. While they will accept the Chinese, despite their poor record on human rights, they will not readily forget that Israeli scientists provided nuclear power assistance to the old Nationalist government. Or that Israel continues to be beastly to the Palestinians.

Oh, well.

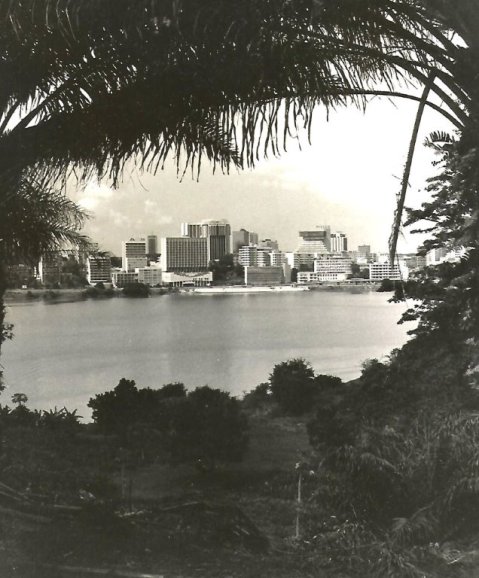

High Noon in torrid Luanda

November in Luanda is a knock-down and drag-out month for heat. Which, like Bermuda’s sandflies and Daytona Beach’s mosquitoes, is not a fact you will see bandied about in travel guides.

By eleven o’clock, even the black Angolans – whom one would expect to be reasonably immune to the situation – are scurrying off to find some respite among the palm groves.

They dart from one pool of shade to the next, criss-crossing streets and alleys as they go, like a terrorised crowd fleeing before some hidden sniper.

One o’clock is the meridian. Now the siesta is fully into its stride, the pavements downtown deserted.

Except for me, trudging along on a pair of fried eggs. Intermittently massaging a neck gone stiff to no avail, from turning to look out for taxis.

And a solitary policeman. Grey of face and uniform, he keeps measured pace on the other side of the street, plainly suspicious of the stranger who chooses to venture out in this sauna weather.

With sidelong glances, we watch each other through the haze that rises from the tarmac. Clomp. Clomp. The sound of our feet is an infraction upon the gentle snoring of the city.

I think this could make a good movie scenario. Then remember that it did. ‘High Noon’, of course. Gary Cooper, the late Princess Grace, and the most convincing bunch of renegades that ever appeared on celluloid.

The vision of Deadwood Gulch (or was it Dodge) grows as we turn a corner, still faultlessly in step, and head towards the old town hall. It’s the heat, naturally, and the silence, the shuttered buildings and the minute hand up in the clock tower, moving fatefully onward.

In my mind, it becomes a game. The cop, gun strapped low, can be Cooper. A little darker and rounder, perhaps, but pure granite underneath.

Me? I’m Tonto, Festus or Pancho. Some such sidekick. Not quite a Cooper but the next best thing. A veteran of shoot-outs and bar brawls.

Striding out to our next showdown, I smile conspiratorially across at my partner. He responds with a frown. Deadwood Gulch fades into reality.

My hotel still being a long way off, I start whistling to lighten the load. The policeman’s frown darkens so I stop. Maybe it’s a jailable offence to whistle during the siesta.

At once, an alarm bell begins to ring somewhere ahead of us.

Cooper, that was, acts commendably in character. The large gun is palmed, quick as a flash. He turns towards me but is persuaded by my idiot expression that I can have nothing to do with this new development.

Together we move towards the sound. The source turns out to be a jeweller’s shop, which fact causes us to exchange meaningful glances.

Peering through the glass frontage, we see the alarm on an inside wall. Its little hammer is beating in agitation. There is no other sign of movement.

The policeman and I confer by way of jumbled sign-language. The front door, we agree – after furious pulling and pushing at the knob – is impenetrable.

But running down both sides of the shop are service lanes. My companion signals that I should tackle one while he investigates the other.

Stumbling past dustbins, I find a small window near the back of the building. It is open but stoutly burglar-proofed.

I chin myself up on the ledge, long enough to gain an impression of a dark room, full of packing cases and broken timepieces. Also to glimpse an indefinable shape – possibly someone’s cap – edging forward above the level of a work-bench.

I drop down, charged with adrenalin, and sprint back to the street, clearing the dustbins like a steeple-chaser.

Taking the bend at full speed, I run straight into the chest of a grey uniform, which clutches me eagerly. Surprised, I stare into the face and, suddenly, the heat of the day gives way to a clammy chill.

It is not my policeman!

Stuttered explanations fall on foreign ears. I point wildly at the interior of the shop and the new cop grunts knowingly. Though he is shorter than my friend, his grip is ferocious.

I consider the circumstantial evidence. A burgled shop, a stranger in obvious flight from the scene. My fingerprints on the windowsill.

Of course, everything will be sweet when Cooper shows up. If he shows up. What if he had taken off after the real burglar? Never to be encountered again? Or not by me, at any rate.

But even as I stand there, with the policeman’s arm around my throat, Cooper emerges from the other lane.

He is carrying a large ginger cat. He drops it as he takes in the scene, stands poised for a moment, then moves to the attack.

A barrage of slaps to the other policeman’s neck secures my immediate release. The invective that accompanies this threatens to curl the paving stones.

The second cop retreats, spectacularly abashed. My friend takes my arm. And together, Cooper and Festus (or Tonto or Pancho) go forward in search of new pursuits.

A cold beer, I feel, would be an adventure in itself.

From One Man’s Africa